Closet ‘Pataphysics

by P.A. Lopez

The stranger leaned forward.

“You’re back.”

Gold-rimmed spectacles caught the light here and there, like butterflies trapped in nets. Walsh could make out the face of a man in his late fifties. Everything about him seemed ordinary in every respect. He could blend, Walsh thought, imperceptibly into any crowd. And yet there was something essentially sad about him; every gesture left one with the impression of great loss, like toy trucks whose paint outlasts childhood, or the wedding pictures that sit on Widow Grave’s bureau beside brass candlesticks.

“Hugged-Too-Late’s the name,” the stranger said with a brisk handshake. “Dr. Hugged-Too-Late.”

“Hugged-Too-Late?”

Walsh peered cautiously through the darkness, where the doctor, crouched, peered back. Outside, the footsteps of the green army swept past.

Walsh had found the closet down an adjoining hallway, thirty feet or so from his cell at Babylon Sisters, Inc. Being small and quick, he had managed to squeeze inside the tiny door (imperceptibly buried in the corridor wall), before his pursuers managed to turn the corner. Collapsed hangers and clothing were draped about them both as they sat at opposite ends of the little room, their knees doubled up and heads bent.

Walsh had found the closet down an adjoining hallway, thirty feet or so from his cell at Babylon Sisters, Inc. Being small and quick, he had managed to squeeze inside the tiny door (imperceptibly buried in the corridor wall), before his pursuers managed to turn the corner. Collapsed hangers and clothing were draped about them both as they sat at opposite ends of the little room, their knees doubled up and heads bent.

“I’m Walsh,” said Walsh, out of breath.

The racket of tripping black boots and colliding knives began to recede, like scarves disappearing up a sleeve.

Hugged-To-Late said, “You were saying?”

Walsh frowned. “But I’ve just come.”

“Horribird, boy! Why fiddle with technicalities? It’s entirely possible that you’ve been here before. In fact, haven’t you been lecturing at me for some time? Maybe you’ve been quite chatty, talking my ear off for an hour, or perhaps you’ve just sat there, trembling all over, white as an egg, as you are now. Perhaps you’ve never been here at all — you avoid this closet and carry on our conversation just the same, or you creep in here only at night and sit for hours, ignoring my company, quiet as a fish.”

Walsh shook his head. “I don’t think so.”

“If you would only tell me your reason for being here, it might clear-up our misunderstanding. I am not an observant man by nature. Still, I can’t help but notice that you are whining under your breath and grinding your teeth — understandably, out of fatigue and terror — that your stomach is growling and that your clothes are ripped (three stitches in the seam of the crotch, the shirt pocket torn and a hole in the left armpit). Really I’m glad you came along to relieve the tedium, even if you do smell badly and need to brush your teeth. Forgive me. It is a small closet.”

Walsh (who was becoming accustomed to surprises) said: “What about you? Why are you here?”

“Hiding from the Cabbage Cutters. Why else?”

“Cabbage Cutters?”

Hugged-Too-Late’s cufflinks twinkled: “Surely you caught a glimpse or two of them at your heels.”

“But I was told there were no guards on this asteroid.”

“There aren’t. The Cabbage Cutters are the private guard of Good King Richard. He must be doing his semi-annual inspection of the premises.”

“Richard?” Walsh gasped. “Then we’re doomed.”

“Well, boy, this is a reasonably safe place, except that here your safety depends not on the change of the guard but upon the change of clothes — a simpler system, I assure you, but indescribably harder to chart.”

“But — we have to go outside sooner or later.”

“Not to worry.”

“You have a plan?”

“No. This door locks from the outside.”

Walsh tried the knob, shook it, then said: “You mean –”

“I mean we have a lot of time on our hands. And you still haven’t told me why you were running.”

Walsh, hesitantly at first, told the Doctor everything that had happened: his appearance at the bank, arrest, interrogation and subsequent escape.

Every so often Hugged-Too-Late would mutter: “Astounding.” “Unique.” “Astronomical.” Or merely: “Horribird!”

When Walsh had finished his story, H-T-L shook his head.

“A horribirdinous tale, dear fellow.”

“And now I’ll never get back home.”

“What? Nonsense!”

“And what makes you so confident?”

H-T-L leaned forward with a suspicious expression. “Could it be you haven’t heard?”

Walsh frowned.

“Our Science, boy!”

“Science?” said Walsh.

H-T-L looked aghast. “Why, The Science — that armrest of the intellect, that great revolving door: ‘pataphysics!”

“Metaphysics?”

‘Pataphysics and Pataphors Explained

“‘PATAPHYSICS: That which extends as far beyond metaphysics as metaphysics extends beyond physics!”

“What does your science have to do with me?”

“Everything. Especially if you plan on making it out of this closet with your brain.”

Walsh gripped his head.

“My brain?”

“Have you forgotten? That Scald Street Spectacle, that Wondrous Affair of Flying Hair: the disembraining machine!”

“I’ve told you — I’m not a criminal.”

Hugg snickered. “Maybe the Babylon Sisters will see it that way.”

Walsh swallowed. “Their machine can’t be that horrible, can it?”

“Worse, I’m afraid. Cleaner than the tomahawk, and — I’ll admit — less painful than the pig-pinching machine, but altogether more terrible than either. So terrible there’s no describing it in casual conversation.”

“Then it really is hopeless.”

“Not with the aid of our Science.”

“Oh?”

“‘Pataphysics is a science we have invented, and for which a crying need has generally been felt.”

“I haven’t been crying about it,” said Walsh. He grabbed the Doctor’s beautifully starched collar, which crumpled like a satin rose. “You said you would help me.”

“And I am!”

“All I want is to return home. Can your Science swing that?”

“Have no fear!” said Hugged-Too-Late, removing Walsh’s hand and brushing out the damage. “‘Pataphysics is the science of imaginary solutions.”

“I would prefer real solutions.”

“Reality is for the mediocre. It’s best not to fool with it when one has discovered there are no real ways out.”

“Sounds optimistic. But what else have I got to go on?”

H-T-L shrugged: “Only that Too-Far Toenail Clipper, that Fatal Papercut, that Bad Rug Burn –”

“Explain your ‘pataphysics.”

“Haven’t I already?”

“But your definition makes no sense. After all, if metaphysics, simply defined, is ‘that which extends beyond physics,’ then what’s the point in creating a term for ‘that which extends beyond that which extends beyond physics’? Doesn’t that make as much sense as saying, ‘further than far away?'”

“You’ve misunderstood. Let us take our Science and apply it to something less general — language.”

“Proceed — but don’t protract.”

“Let us take as our physical basis a phrase or image described in a work of fiction. Something simple, unimpeachable of itself. ‘The moon rose over the sea.’ We label that statement physical. For though a literary work may be a lying little devil in the sum of its parts, we cannot deny that the words on the page say what they say, even if that statement is later cast in doubt.”

“Continue.”

“Metaphor, on the other hand, is a metaphysical device. ‘The yellow eye rose over the sea.’ Although the moon (physical) is still implicit in context, an eye now temporarily occupies its narrative space. But the moon remains the dominant element, the eye a precipitate of the physical, intended to embellish it. Still with me?”

“Yes.”

“We will allow then, for the sake of our Mr. Walsh’s education, the coinage of a simple term: the pataphor. What if our phrase were to read: ‘The yellow eye rose over the sea: in time, a tear fell, beading along a whisker to fall into the blue porcelain dish.’ Having taken the precipitate of our physical object seriously (the eye given form), we have delivered that precipitate into a new context wherein the precipitate becomes the physical. The moment of pataphor occurs when the metaphor has become so embellished it no longer relates to that which it was meant to embellish.

“Ergo:

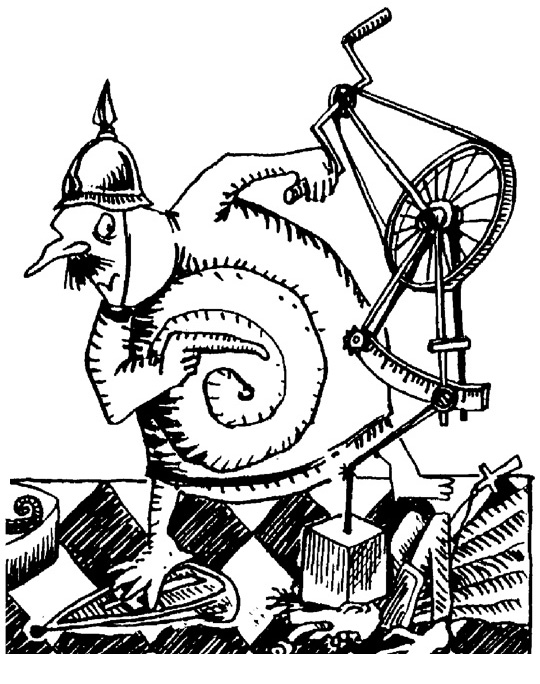

“PATAPHOR: That which occurs when a lizard’s tail grows so long it breaks off and grows a new lizard.”

At this Walsh tried to stand, hitting his head on an elevated shelf.

“Ow! I see now: as far from metaphysics as metaphysics extends beyond physics. Imagination based on imagination!”

“Bravo!” cried Hugged-Too-Late, clapping Walsh broadly on the back. “Transformation is the stethoscope of ‘patascience!”

“Let’s make some pataphors then.”

“Very well. First we need a dramatic situation. Let us say, for the sake of pataphor, Tom and Alice and typical high school freshmen, who also happen to have crushes on one another. Now suppose I say: ‘Tom and Alice stood side by side in the lunch line.'”

Walsh thought a moment, then said:

“Then I might say, metaphorically: ‘Tom and Alice stood side by side in the lunch line, two pieces on a chessboard.'”

H-T-L nodded. “And I: ‘Tom took a step closer to Alice and made a date for Friday night, checkmating. Rudy was furious at losing to Margaret so easily and dumped the board on the rose-colored quilt, stomping downstairs.'”

Walsh laughed.

H-T-L said: “You laugh, but it’s a sad game we’re playing. After all, Rudy and Margaret are but the stuff of pataphor. Everything about them (their wooden chessboard with the nicks on the pieces, Granny’s faded quilt, the carpeted stairs of their suburban bungalow) bear no relation whatsoever to our date-makers at Green Candle High. Whether Tom and Alice fall in love or fall asleep, we will never know Rudy’s last name and, indeed, have no reason to care.”

Walsh smiled wanly. “So who won the game?”

H-T-L shrugged. “Tom won.”

“Yes,” said Walsh. “But unfortunately, only in pataphor.”

“No,” said Hugged-Too-Late: “in metaphor. In reality, the game (love) is in progress. In pataphor, Rudy lost.”

Walsh leaned back into the hangers, which tinkled liked glass wind chimes.

“Let’s try another.”

“Very well,” said Hugged-Too-Late. “Your turn.”

Walsh thought a moment. “‘The sweaters are hanging in the closet.'”

“‘The sweaters are hanging in the closet, their profiles the silhouettes of elephants.'”

“‘The sweaters are hanging in the closet, their profiles the silhouettes of elephants at the Municipal Zoo before Mr. Bigby’s five o’ clock show.'”

“Not bad,” said H-T-L. “But I pity our poor Bigby, begat of shawls and sweaters.”

“You sound disappointed,” said Walsh. “What were you expecting when you thought of elephants?”

“The circus. I love the circus.”

“More?”

“One more,” said Hugged-Too-Late.

“I say: ‘My heart skips a beat.'”

“And I: ‘Your heart skips like a checker.'”

“‘My heart skips like a checker, landing at the end of the board. King me.'”

“More board games. A game of checkers begun in the chest, terminating in metaphor. (The second checker was pataphorical.)”

“So the pataphor creates its own context.”

H-T-L nodded.

“But what does this have to do with me?”

“You have to understand another concept of ‘pataphysics first. …

The Trapeze Artist

“‘Pataphysics will examine the laws governing exceptions, and will explain the universe supplementary to this one; or, less ambitiously, will describe a universe which can be seen — and which perhaps should be seen — in place of the traditional one, those laws that are supposed to have been discovered in the traditional universe being but correlations of exceptions, albeit more frequent ones, but in any case accidental data which, reduced to the status of unexceptional exceptions, possess not even the virtue of singularity.”

“How do you intend to explain this one? More pataphors?”

“Not this time. Apply what I’ve just said to your situation! Can you deny that those laws we have supposedly discovered in this universe are but correlations of exceptions?”

“I don’t understand.”

“You will. For now it behooves us to speak of the agony of the trapeze artist.”

“So we’ve come to our circus at last. And I thought we were going to discuss laws.”

“But we are. It is appropriate that we liken the subject of our argument to a trapeze artist. Let us see him, in our mind’s eye, as he swings from bar to bar over the center ring. The circus tent represents our universe, and the people in the crowd — the plump lady with the ice cream cone, the young couple with their baby (three months and teething), the schoolchildren with Ms. Barnes — represent mortal mankind.”

“I’m game.”

“Good. Then let us ask our trapeze artist to step to the landing and play a part in our little spectacle.”

H-T-L executed a little bow and began afresh.

“Here on earth, we are witness to a variety of phenomena, some explainable by science, some less so. Mediocre, indulgent scientists tell us that our world is based on laws that, by their very definitions, have no exceptions. If this is so, however, many things remain unexplained. For instance, if we put credence in a universe based on laws, there is no way to account for your presence on this asteroid.”

“But I am here.”

“Precisely. In a universe of laws the trapeze artist represents the law and must always catch the next trapeze. He has no safety net. If he falls once the show is over. All it takes is one exception to one law to prove decisively that the very foundation of that system is flawed. Having happened to you what has, you can no longer believe in such a system.”

Walsh looked glum.

“So what should I believe in?”

“How much more appropriate to see our universe not as something governed by laws but as a place where anything at all can happen. Everything that occurs on our world is exceptional, a freak accident — gravity, matter and energy, consciousness — only some exceptions are more common than others, a fact that doesn’t speak much for them, since, at base, they aren’t even exceptional exceptions! In this version of the world the trapeze artist always misses — plans on missing, is expected to miss. Every time he falls into the net is presence is recognized on earth by showers of oohs and ahhs. Every apple that drops is another blown stunt. We see a lot of our man Gravity, and no wonder: he is a lousy flyer. He’s so bad, in fact, we’ve mistaken his clumsiness for skill.”

“So why am I here?”

“I was getting to that. The phenomena we never see are the most skillful. The ones that make lettuce grow hair, bowling bowls lose holes and turn suitcases green. They pass peacefully over our heads, falling to earth once every million years, perhaps even more rarely. My guess is that one of these has landed, right in your birthday cake, one of these exceptional exceptions — and hopefully will return to obscurity soon. It is also possible that your life until now has been a mistake — a good flyer having a bad stretch, who, for the first time since your birth, is in better form. Of course there is also the possibility that no new phenomena have fallen, and your trapeze artist remains in poor form as always. In that case you were meant to be here all along. Another, better flyer has only entered the show and for the time being is catching yours by the legs. If that is the case you want to get that second flyer out of the picture.”

Walsh sank a few inches.

“If what you say is true — if my life until now has been maintained by accident — it could take a long time for that accident to be reinstated.”

“Forever, most likely,” said Hugged-Too-Late. “For all practical purposes at least.”

Walsh’s ears turned red.

“You haven’t helped me at all — only made me feel worse!”

“Read the writing on the proverbial wall, boy! Have you forgotten so quickly? Imaginary solutions! Isn’t that what we’ve been talking about? Remember, above all ‘pataphysics will study the laws governing exceptions. As of this moment we must do precisely that: research exceptional phenomena, trying to discover which phenomena it was that sustained your former existence, and, now that it has failed (or something else succeeded) discover what we can do to set things right.”

“But how are we supposed to study these exceptions? And what about these imaginary solutions? What if your trapeze artist has simply gotten tired of flying? And how are we supposed to get out of this closet! Imagine our way?”

“Don’t be absurd,” scoffed Hugg. “For physical problems we shall employ physical solutions. Pataphysicians always come equipped. And it just so happens that I have remembered to bring — by means of our Science of ‘Pataphysics –” he took something from a back pocket: “a hairpin! Now watch as I demonstrate how this instrument greatly facilitates the opening of doors.”

And with that, he did.

##